City Nature Challenge - Martinsville 2021

by Noel Boaz

Martinsville participated in the 2021 international “City

Nature Challenge” organized by iNaturalist

(https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/city-nature-challenge-martinsville-virginia)

over a period of four days, April 30th to May 3rd. All Virginia Master

Naturalists were invited to take part by e-mail. To participate, individuals

used their cell phones with the free iNaturalist app and followed the following

three simple steps.

Globally, over a million observations were made and uploaded

by some 52,777 people over the four days of the City Nature Challenge,

resulting in some 45,399 species of animals and plants identified. In

Martinsville, the Challenge was taken up by seven individuals, four of whom

observed, photographed, identified, and recorded a total of 31 species of

vertebrates, invertebrates, plants, and fungi (figured below). This was a good

showing, besting the likes of Darwin, Australia and Dubai, UAE, which each

recorded 13 species, and with more observers. The San Francisco Bay Area of

California, where the City Nature Challenge originated, took overall honors

with 2885 species identified by 2265 participants.

A map of the species identified shows that observations were

clustered in a relatively constrained area of around 2 square kilometers in

uptown Martinsville, not far from the Virginia Museum of Natural History. This

area encompasses a topographic high along two ridges that follow Church Street

and Starling Avenue, respectively. Elevation varies between 1050 feet above sea

level to a low of about 960 feet above sea level for some species

identifications along the central portion of the Dick and Willey Trail adjacent

to Poplar Spring Creek (parallelling Northside Drive).

In a very general way the species observed in the

Martinsville City Nature Challenge mirror the ecological diversity seen in the

larger environment. About three-quarters of the species recorded were plants,

autotrophs which synthesize their own food from inorganic elements using the

sun and carbon dioxide, producing oxygen in the process. Plants and other autotrophs,

such as aquatic algae, are the primary producers of biomass on the earth. The

other species observed are all heterotrophs, or species which must have organic

food molecules to exist. Insects and birds made up 6.5% each, and mammals,

fungi, and “other” made up 3.2% each of the observed and recorded species.

All the species identified have fascinating stories to tell, weaving a far more intricate narrrative than simply announcing their presence. A few of the species discovered, and how they relate to the ecology, biodiversity, and evolutionary history of our area, are described below.

Ivan Hiett photographed this patch of Lemon Balm (Melissa

officinalis) in J. Frank Wilson Park in Martinsville. His identification

was confirmed on iNaturalist as of Research Grade. Lemon Balm is a member of the mint family (Lamiaceae) and its

name is from Greek for “bee [leaf]” and “from the [pharmaceutical] office.” The

species is originally native to the eastern Mediterranean area where it was

used both to attract honey bees to hives and as an herbal remedy for maladies

ranging from heart problems to depression. Lemon Balm spread throughout Europe

in the Middle Ages and eventually to the U.S., where it is recognized as a

naturalized species. It is known to have been cultivated at Monticello by

Thomas Jefferson.

Mark Caskie identified this stand of ferns (Class Polypodiopsida) in J. Frank Wilson Park in Martinsville (left). Ferns have been growing in what is now Virginia for a very long time. Fossil ferns from the Pennsylvanian (Carboniferous) coal beds of Southwest Virginia date from 299 - 318 million years ago (right). Because their basic form has changed so little over that immense span of time, ferns are sometimes referred as “living fossils.”

Fungi, including Bonnet mushrooms of the genus Mycena,

shown here as identified by Lynn Pritchett on East Church Street in

Martinsville, used to be considered plants. But as more has become known of the

genomics of fungi, they have been placed in their own kingdom, of equal

taxonomic rank to Animalia and Plantae. Like plants, fungi are fixed to a

substrate and do not move about, but like animals they are heterotrophs -

living on primary producers like plants. Here these bonnets are growing on a fallen

and decaying tree.

The species was originally named in 1770 from a specimen from

Dinwiddie County, south central Virginia, by Dru Drury, an English natural

historian, who had been sent it by an Anglican minister, the Rev. Devereux

Jarratt, Rector of Bath Parish. Its name translates as “smooth armor” in Greek.

Aphelora is a detritivore, eating decaying vegetation

on the forest floor. A recent paper reported the fascinating discovery that the

species can be infected by a parasitic fungus named Arthrophaga myriapodina,

which causes infected individuals to climb to an elevated spot as they are

dying so that spores of the fungus can be dispersed by the wind

(http://dailyparasite.blogspot). com/2017/10/arthrophaga-myriapodina.html).

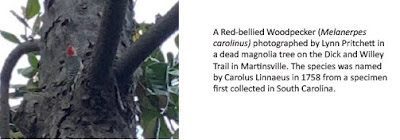

The City Nature Challenge also offered even a bit of vertebrate synecology. Martinsville has an abundance of large trees, which are focal points of ecological niche overlap for two vertebrate species observed, the red-bellied woodpecker and the eastern gray squirrel. Both species live in large trees and compete for prime hollows and nesting sites.

The 2021 City Nature Challenge, an international bioblitz, involved 419 cities in 44 countries. The event is organized by the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, and is described as “an international celebration of biodiversity in and around urban areas.” Six Certified Virginia Master Naturalists from the Southwest Piedmont Chapter - Noel Boaz, Mark Caskie, Gael Chaney, Christy Deatherage, Ivan Hiett, and Lynn Pritchett - took part in the event. Thirteen identifiers from iNaturalist confirmed the identifications.

Martinsville is already signed up for the 2022 City Nature

Challenge (https://citynaturechallenge.org/), which will take place from April

29 to May 2, 2022 (observations and photography) and from May 3 to 8, 2022

(identifications). Taking part counts toward VMN service hours as a

citizen-scientist. Watch for details on how to sign up!

I tried to enter the bluebird nestlings that I photographed while monitoring bluebird boxes, but a few days after the challenge, I discovered that the observation had not uploaded during the required time frame. I guess those observations didn't count.

ReplyDelete